Network Address Translation

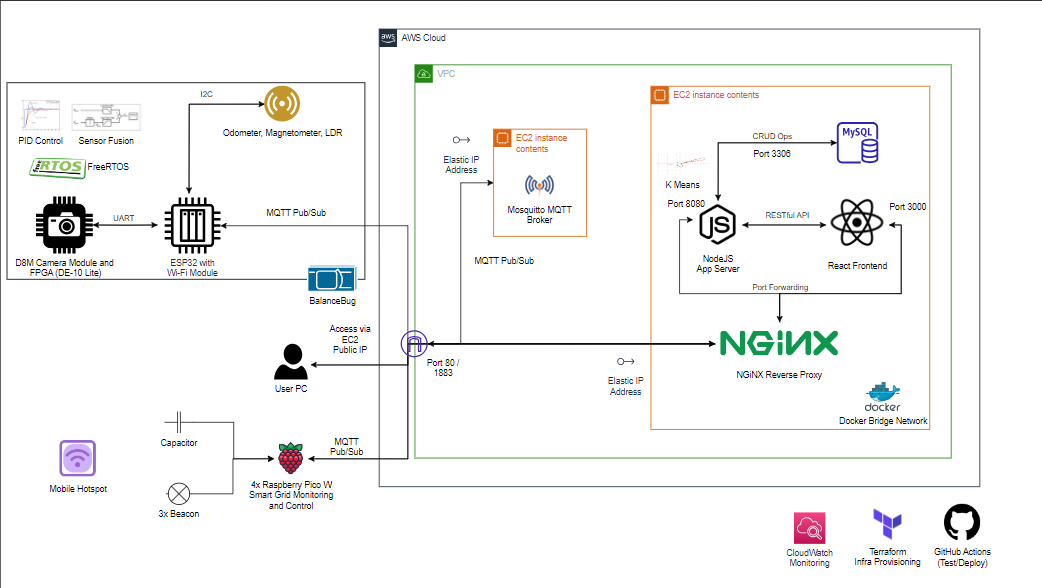

I had the opportunity to plan and implement the software architecture for our Year 2 Project. We had a rather elaborate software setup; in the words of my teamate, a little ‘overkill’. One aspect of this work included networking and implementing APIs to ensure connectivity across all devices in the architecture. The devices we used included four Raspberry Pis to control a ‘smart grid’, with 3 beacons to perform trilateration and 1 supercapacitor to regulate the grid’s voltage level. We also had a ESP32 WROOM DA on our rover.

Originally, I had intended to use REST APIs across our entire architecture. This was meant to standardise how our devices talked to our servers and vice versa. Soon however, we stumbled into a roadblock. I should have realised it earlier, but was prompted by a teamate. We had bumped into the NAT Traversal problem. How would our IoT devices, without static IP addresses, communicate with the servers? The servers had a static IP address thanks to an AWS EC2 Elastic IP Address, but our devices (connected to my mobile hotspot) did not.

Our devices have dynamic IP addresses because of a technology called Network Address Translation (NAT). To conserve the limited number of IPv4 addresses on the public internet, our routers perform NAT, which means that they map private addresses inside a local network to a public IP address. But these external public IP addresses are not fixed.

So, I struck to find a solution.

Solving the Problem

Solution A: Port Forwarding

This was dropped quickly as we were reliant on mobile hotspots to act as routers and connect our IoT devices to the internet. These mobile hotspots are not configurable and hence port forwarding was not feasible.

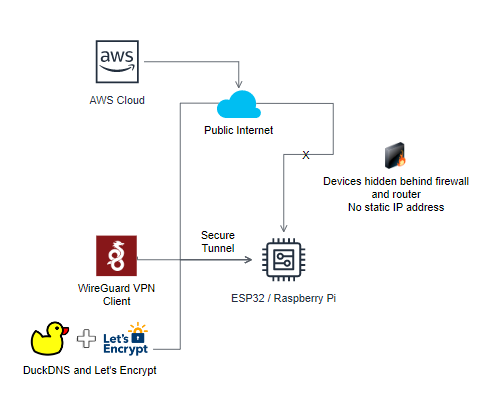

Solution B: Reverse Tunnel

This could be done by setting up a Virtual Private Network (VPN) connection between our Node.js server and the IoT devices using a service such as Wireguard and a Dynamic Domain Name Service (DNS) such as DuckDNS to fix the endpoint address; this was because the router’s Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) would continually reassign IP addresses each time. Only one port is opened, with all connections pre-authorised and requiring authentication. However, this was not feasible due to the limited compute capacity of the Raspberry Pico W, which was unable to handle the cryptographic requirements of a VPN.

Solution C: Local Area Network

We could connect devices via Local Area Network to the server on localhost. This solution was thoroughly considered and even tested but dropped in view of its low availability and reproduceability. Furthermore, if localhost was used, the team would have to keep turning the server on and off. This was not a sustainable approach to solve the problem.

I had also looked into configuring MAC VLANs on Docker to achieve this functionality, but realised this only works on Linux (which is not the OS that I use to develop, unfortunately).

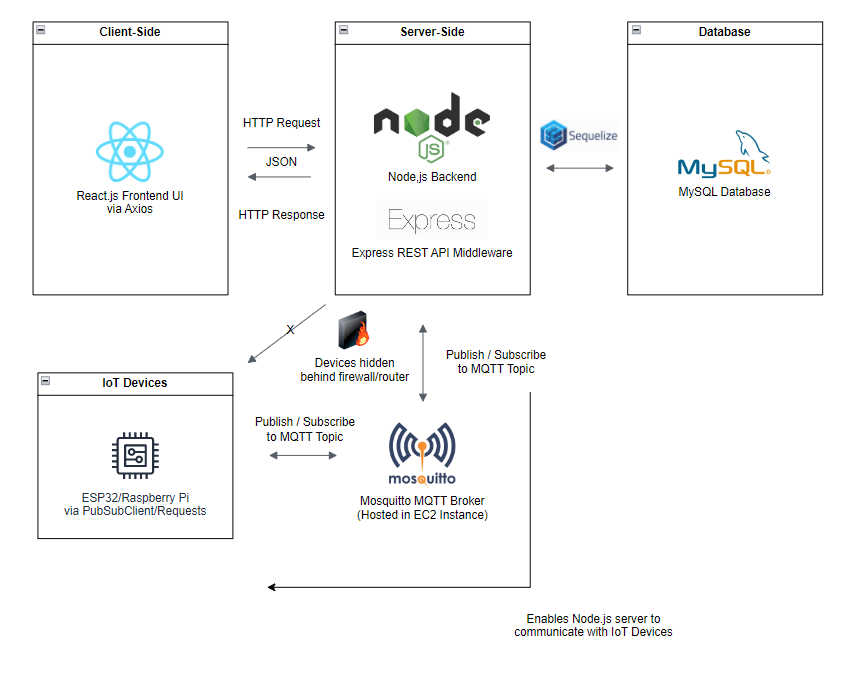

Solution D: MQTT

So, we overcame the problem with the use of a MQTT Broker. By setting up another EC2 Instance containing a Mosquitto MQTT Broker, we were able to establish bidirectional communication between our servers and the IoT devices. The IoT devices would publish to a topic to update the server in real-time.

From then on, we used MQTT for the project - one crucial part of the integration puzzle that we spent many nights solving.

Check out our GitHub if you want to read up more about our project.